Beauty’s the hermetic cell of thought. It is the chamber made for dreaming minds, for ruminative ease, for inward turns that laze into the comfort of implausibles of possibility—for the meditative pleasure of the eye. The air of it is rare, the speculation braced, the circle of its charm the carved perimeters of grace: a haven that is respite from the blazing of the world. Like a breath held, a moment into hold, a time that’s stalled of time, to attend to the enthrallments of the thought and the ceremony of awareness: the ballet of the lilting of the mind, the drifting of the senses, the formulated dripping of the sensuously through. Only computations know this false, but geometers are true, for the transformations born upon the imprint of the glass, like Stevens’ jar of Tennessee, augment the fall of lines and the intensities of shades. The world surrounds the dreaming mind, but for the dreaming mind. And arcs of glass, it magnifies, and haunts the gaze with hidden waves, and movements on a curve’s a fall of grace: a comportment of the mind, a posture of the seeing soul, a dignity within—the personal of self composed as style. Within the districts of contemporary art, there is nothing so beautiful as the art of Joseph Raffael. There are no other contenders in the face of his continuing achievement. In exhibition after exhibition, Raffael demonstrates, like the master of the art that he is, the sheer entrancing beauty that can be achieved through the use of watercolors—his exclusive medium. In exhibition after exhibition, Raffael displays monumental executions of delicacy and dexterity that seem to defy the possibilities of the medium, to prove, like the master of the art that he is, that our expectations of the limitations of the medium are naïve, that only someone who has devoted his life to learning the ways of a knowledge and a practice can show us what is possible. And in exhibition after exhibition, Raffael tells us, like the master of the art that he is, that beauty may be easily spoken of and theorized about, but like all things too easily transposed into theory, the truth of them is clear only upon direct encounter. To know what beauty is, we must drench ourselves in the beautiful, and that requires a Raffael. And it requires a Raffael to show us that beauty prevails, and to show us the ways in which it prevails, even as it is brought into question by minds that think where they should feel, that theorize where they should wonder, and submerge, and take note. Beauty is much under question now, and is easily questioned when one only thinks about it. It is no longer much the objective of contemporary artists, and has not been for decades, for long ago visual art turned largely to the cleverness of the implied concept in place of the captivation of the visual imagination—to the literary imagination stoked by the visual presentation. Beauty has come to be viewed as the result of convention, as determined by cultural specifications, as a product of inurement—we are captured by the shimmering glow of what our culture instructs us should be seen as shimmering and glowing. And at its worst, until worse comes, beauty is taken to be a Trojan Horse—the glittering wrapper, the gaudy drapery, within which is carried the prevailing ideology, sold us by the dazzle of the packaging, carried like an infection to the depths of the pretty tissue. To doubt beauty in this way is to make it a function of something else—of culture, of ideology, of salesmanship. It is to make beauty an aspect, an attribute, an adjective—the beautiful—rather than a noun. It is to doubt that beauty is something in itself—that beauty is. If there is an issue regarding beauty, then it is a personal matter with regard to Raffael, for his work is the focus of the issue in our time, his work is the heart of the issue. To doubt beauty, even to doubt its appropriateness of place in contemporary art, one must doubt what he does—in exhibition after exhibition. The current exhibition is as much to the point—to his point. It is, again, what we expect to see, and for those of us fortunate enough to know his work, work that is far from known well enough around the world, what we depend on seeing from him. The exhibition is intended to comprise 15 paintings, the brunt of the work done by Raffael since 2005, the year of his last exhibition at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery—all done in watercolor on paper, all of astonishing scale, considering the medium, the largest of them measuring 85 inches wide. (This essay is being written in advance of the exhibition, after the author was permitted to view the works at length.) And they are all depictions of nature scenes, as is typical of Raffael. But there has been a shift in the orientation, a shift that began in the midst of the work for the 2005 exhibition, for which this author wrote the catalogue essay, and is fully realized here. Many of the precise subjects are the same as they were prior to 2005—there remains a devotion to floral painting, to the intricately noted details of blossoms, and to observing birds sitting on branches. But otherwise, where there was previously a tendency to see serene moments in nature—fields of fallen leaves, lilies lying on the surfaces of ponds, spreading trees—now there is a penchant for the animated in place of the placid, now there are fish swimming beneath the surface of the waters and rising above it, and the birds are more alert, more active, more agitated. And there is something else, something else that is different, more active, more agitated, more energized. Raffael’s watercolors continue to have every signature element of his style. They are glistening, intricate, limpid renderings of nature, gem-like in the purity and brilliance of their colors, deeply intimate in the complexity of detail that is never falsified, that is rendered with all the specificity that exists in nature. Look at Autumn II, 2006, and Another Spring, 2006—two large images of trees in full foliage in which every leaf is present. In the past, Raffael has employed the effect of an impossible depth of field—he showed us receding vistas in which everything, regardless of its apparent distance from the observer, remained in perfect focus. It is an implausible form of vision—literally impossible for the human eye—and although there are no deep vistas here, the effect of his intricacy of detail remains the same. These images may seem like re-creations of normal sight, but they are not. This is visionary, for no ordinary mortal sees like this. And there remains the ideal fusion of technique and subject matter, the simultaneity of the image of nature in its every detail and the brush stroke, the spread and infiltration of the watercolor applied, to some degree, wet on wet, the slight migration of pigment to the edges of the stroke. The scene and the technique become, everywhere, one and the same. Raffael’s manner of applying watercolors to the paper is ideally attuned to what he is painting, as if the manner and the matter were one, as if paint and leaf and petal and feather and bark were indistinguishable by nature—as if he painted with the movements of nature, painted with nature itself. What is new here, what has blossomed since Raffael’s last New York exhibition, is a dynamism, a sheer energy that his images did not have before, that his style did not have before. There has been for many years a certain placidity to Raffael’s images, a certain calm and easiness to the tonality of the renderings. In much of his subject matter, it was as if nature had sat for her portrait. In all their intricacy, fallen leaves laid in their fields, forest vistas stood with an august dignity against the air, flowers arose in their vases and turned their best face. There was an air of deep mystery about it all, and a sense of waiting on the part of the nature scenes and the viewer, as if holding one’s breath for a realization about to occur. All seemed to be waiting, attentive and alert. And the manner of painting suited the tone—the sureness of touch and application of watercolor carried through the calm sureness of the imagery. All waited to have its secret revealed, and it waited with assurance. Now, there is an energy to the painting and to what has been painted. The brush strokes have an eddying fluidity and a sinuous swiftness of movement that seems inimical to a medium so delicate and requiring such sureness of hand, a medium so unforgiving of errors of touch and physical judgment—and would be at odds with the medium if executed by a hand less sure than Raffael’s, by the hand of someone less than a master. The backgrounds begin to break up into abstract patterns of movement and color, of swirl and hue, the limitlessly distant depth of field in the receding forest is often gone, and jewel-like brilliancies of color have taken its place. The colors have become somehow denser. They appear to have been ramped up not only in hue and value but in intensity—Albers’ third quality of color, other than its place on the color wheel (hue) and its gauge from light to dark (value)—the sheer glowing potency of the colors seems to have been amplified, as if they are now what they have always been, only much more so, as if they were more themselves, to a degree ultimately blinding. There is a shiver to it all, a vibrancy, a universal vibration, or set of vibrations, running through everything that greets the eye. There is a tension of explosive power. The aptness of technique to content, of the means of rendering to that which is rendered, continues, and both have been amplified. As the colors detonate in the vision, as the strokes assault the senses, senses beyond just the visual—you can feel these paintings along the spine—the birds on their branches pulse and resonate, bristle and raise up their wings like a snarl, or an astonishment. Flowers seem to erupt like novae in the distance of space. Autumn leaves spill and pour around the tree branches like a maelstrom. Fish break the surface of waters like geysers. And flowers seem not illuminated but coalesced of light, going to white-out at their points of greatest, thickest physical density, where their petals are most material. Consider just a few of the paintings in this exhibition. Spirit, 2006, is a scene of a pond filled with fish, comparable to several Raffael has painted in the past but far more activated than before. The fish break surface everywhere, as if spawned of paint, and a clouded sky is reflected in the surface of the water, letting through a partially washed out vision of what’s below, as if the immensity of the atmosphere had been poured into the pond. Rippling networks the surface of the painting, capturing and dispensing light reflections from the sky, integrating earth and the heavens, water and the light, above and below, and integrating with itself to constitute the real subject matter of the painting—a field of pulsation that only incidentally and surreptitiously testifies to living beings in their environment, living out their lives. Where the paper crinkles—one of the inevitable effects of the employment of watercolor, and so an effect to be turned to effect, for craft is the use of inevitability to a purpose—the apparent fish of the depiction flutter with the wavering of the water they appear to swim beneath. It is all controlled, and it seems all barely controlled, and it is all of a piece—all a field of energy captivated. Emergence, 2006, is a portrait of a single flower set against an abstract background of roiling strokes of pure color. And the active principle of the strokes of the background is the active principle of the strokes of the entire work—it all boils before the eyes. And the flower itself is nothing sedate, nothing sentimental. The color of it seems to stream from the center of its self, and at the point of its birth, at the point where the petals emerge from the stem, there is a volcanic explosion of incandescence, a star burst of light, the limiting condition of the real, pouring out into the living presence of the floral burst. Aptly titled, this is not a portrait of a flower, but of the very principle of emergence, the very quality of growth—something serenely accepted by us and all but incomprehensible the moment we consider it—observed in the natural setting all around us, observable everywhere.

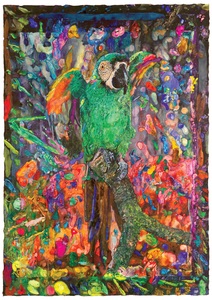

There is in all this a lesson about beauty’s nature. Beauty is not a felicity to the eye, not an agreeability honed unto delight, not a portioning of pleasure, not as pleasure is conceived to be the quality of what we hope to have from the affections that we find in life. That is not what affection, not what art, and not what beauty are about. That remuneration of the spirit, that recuperation offered to a lack, has no bearing on the thing. It is too much a fantasy consecration of the truth to our centrality, to the answering of our needs. Our needs count for nothing in this field—we are not the foundation, we are not the reason. Beauty is the vitality, for beauty is the vision heightened, amplified to recognize a nearly violently creative creation, an eruptive growth of field, a detonating field of growth. And underlying it, a principle of formulation that dwarfs our being and our needs, a principle whose scale cannot accommodate our diminutive stance. Beauty forms to galaxies as much as to the buds, as much as to a woman’s breast, as much as to a man’s Blakean fist. Susan Sontag once observed that “every style is a means of insisting on something.” Raffael’s style has become one of pure insistence, a forceful pronouncement in liquid hues and the seeming tentative of paper of what he has observed, and what he keeps observing—of what we need to see. His insistence is palpable. It ripples like waves, it hums like visible oscillations, it silently howls like wind. It blazes like light. And what we see, what we are shown, and what we learn, is that beauty is the potency, the power, the electricity of life. And not just life, for the energy of vision runs through everything we see. The beauty of these works is the dynamism of the field, a field like a single pool of water glistening across the surface of a painting. It is the vision of the vitality of existence, the ardor of the real. One can see it clearly in a work such as Renascence 2007, 2007. Consider it—a painting of a parrot on a tree branch, but hardly that. The parrot raises its wings as if alarmed, and it stands against a background that should be forest but is instead a seething expanse of abstract form—colors in hallucination, hues that chime like a welter of the bells. And the wings of the parrot, raised in awareness, lifted in alert, blend into the background—it is impossible to find their edges, to see where they leave off and the background fills in. The parrot is visually emerging from the field—this, too, an emergence. It arises from the welter, the welter into which it eventually will submerge, as will we. All is of a piece, and the severe depth of field Raffael has used in the past, to fuse together foreground and background, has become a universal extension of pulsating energy. As much is true of the more sedate, of the flowers in their vases, of the heaps of fallen leaves from years ago—of the stabilized of form and formed to wait. Even the still of vista and still life gives form that is the bristling of mere fact, of fact not so mere. The stabilization of sheer factuality, of static, modeled form, has always been sheer force of Being—Being as a dynamism of the power to sustain itself. For form is not just form, not just inert. It fills in from behind. Presence itself, maintained moment after moment, is itself an insistence, a style, a formulation that does not lie still but is recreated, moment after moment, by the streaming force of Being, the power reconfiguring in constant push to be. The need to see the pulse of energy on the surface of the work is precisely that—a need. And it is a literalmindedness, as if one could not conceive of that which is implicit. And the counter-argument is circular: if Being, that which is, is just inert, just is, it is sustained by what? On what does it reside? Which is to say the nature of beauty in Raffael’s work has not changed, for beauty of this hue was always there. The vehicle of its delivery to our eyes has been augmented by the artist, but the point remains the same. It fills in from behind. If the dynamic of beauty were something new, if it had not been before us all along, it would be mere therapy—a reconfiguration of the receiving sense, its only result the petty remuneration of the perceiving soul, a vision solely for the sake of the reconditioning of our senses. But if it is a fact of things, then it always was, and a hand and eye so keen as Raffael’s have always given us the view. This is, of course, the Dionysian—the active agency of churning fields, the raw fecundity, the generative seething, from which the reification of the tangibly formulated must arise, into which it must be subsumed, of which, in the final assessment, it always is. And what we find in Raffael is that the formless dynamism of the Dionysian and the beautiful form of the Apollinian were never parted, never simple alternatives. They are a matched pair, as are all dichotomies, inseparable, each inconceivable without the other, each impossible alone—as impossible of division as the opposing poles of a magnet, for if they were separated, there would be no magnet, there never would have been. Opposite ends of any spectrum infiltrate each other. They are intricated. And the beautiful image is animated by the power that sustains it, even if that animation is, for a time, its stable, constant, vibratory re-creation, pronouncing it through time. But it is we who conceive the re-creation; it is we who note the spectral separations, flaming like a galaxy of gems. And beauty is a vision, a way we see the constant reformulation of change—one of the ways we see. It is a clarity of vision, an eye rising above the waters, a capability of sight rinsed clean, a comprehension of what we cannot conceive. It is a grace of visibility. And as the encountering of art is a psychological event, as psychology is anterior to aesthetics, beauty is an event of life—a moment in the mind. The vision of beauty is vigor answering to vigor—nowhere a need—in fact a reconfiguration of the self in a response to its like, responding to the sustaining power of the real. And so, beauty is not a recompense, not an answer to the faltering of humankind before the truth of things. It takes upon itself its opposite. It embraces the change of rise and decay. It incorporates all that we must confront. It embodies the whole of life. And the vigor of it as a vision is a strength, a strength drawn from the force of its insistence, the potency of its style, the indelibility of its form. And as all fear is ultimately the same fear, all strength is the same strength: the strength to exist, to be, to confront all the aspects of existence, without the need of fantasies, without the flinch before the facts—the endpoint of self-betrayal. Beauty is the courage to live. And so beauty is the fracture in the glass—the swarming inchoate showing through, welling up from behind, forming and fortifying the vision. It is a vision that has gone beyond the perfect to embrace the flaw, to encompass the crack in the veneer, and we have long known that beauty is the proper portion of the broken hearted—it is strictly they who know its worth, it is they for whom the enhancement past perfection can be cherished. This is what Raffael shows us, what he was born to show us, so deeply of his own nature is his vision. In his indispensable art we see the cracked surface of nature that is nature whole, the riven heart of the world that is the world vibrant and teeming with life, the energy of creation that is the only fact of nature we will ever be. In the compass of his art, in the braced and tempered serenity of his atmosphere, the speculative mind is hastened to freedom, and the blazing of the real is in-folded into grace. In the compass of his art, the broken heart of beauty finds the rose. And in the compass of his art, those who know the damage that endows are made whole again.

© Mark Daniel Cohen—Nietzsche Circle, 2007 (published in Hyperion: On the Future of Aesthetics, a web publication of The Nietzsche Circle, October 2007) To download the entire essay: “The Dynamism of the Beautiful” |

||||