"My soul is from elsewhere, I’m

sure of that,

and I intend to end up there.

—Rumi, “Who Says Words With My Mouth?”

Trans: Coleman Barks

There is something becomes of master artists as they progress. Throughout the history of the arts, throughout all the major art forms, we find artists who enter a stage of their work in which a change comes over the art they have devoted decades to making their own. Something new arises—often something utterly unpredictable, as often a further progression of the course they have been taking all along—but it is always a change that seems astonishing. And it is always a change that seems the fulfillment of a promise, as if after the long years of perfecting a style, a more perfect approach to art makes itself evident.

We see it rarely and only in the masters of the mode. We have found such changes of manner, such renewals of perfection, in the last sculpture of Michelangelo, in which he moved to incomplete figures embodying gestures of articulated ardency; in the poet W. B. Yeats, who evolved to a hard, seemingly granite emotionality bereft of all easy sentimentality; in Shakespeare, who found in “The Tempest” a profound ease that follows the composition of the most harrowing tragedies in our literature. We have seen such transformation in Mozart’s late, dark symphonies, in Titian’s last forms dissolving in the maelstrom of his brushstrokes, and in T. S. Eliot’s final turning toward mysticism. There seems to come to some artists an ultimate revelation, a distillation of the artistic vision, a rinsing of the eye of the creator, as if finally the long years of mastery turned out to be an apprenticeship and the truth of the art comes to bloom like a late-summer flower. The blossoming of that rose brings to us a realization that is indispensable: the art that had required so many years to reach its zenith becomes purified, relieved of all extrinsic matters, delivered of all infiltrates, of all peripheral concerns and superfluous habits of imagination and vision, and there is disclosed to us a purged, cleansed, unencumbered art, an art that seems as if the first art—there is revealed to us what art truly is.

Such moments in the chronology of a profound creativity force a question: “What art does one create when one has finally made one’s way home?” The evidence of these works makes clear that there are works of art and a sense of art that can come in the second half of an artistic career and that can be achieved by no other means. These are the works of maturity, the works of hard-won ability. In a time of general, culture-wide, even world-wide fascination with youth, there is a lesson here that we should acknowledge: we should turn the greater part of our attention from innovation to experience, for there is a vision that arrives in each field of creative endeavor only, and only occasionally, to the master artists of the mode.

Joseph Raffael is a master of such caliber—for more years now than anyone has an excuse to fail to recognize, he has been the most accomplished watercolorist in the contemporary art world—and the works in his current exhibition constitute a modern instance of this ultimate insight, of the renewal of the delving power of creation, of something thought perfect perfecting itself. His subject matter remains what it has been for many years—garden scenes and forest settings, flowers flourishing in the wild and settled in vases, ponds with fish drifting just below the surface, the play and lacing movements of water, birds blending in among the leaves. Yet there is something tangibly different, something fresh and distinct. These current works appear denser, more precise, more fully conceived, realized, and concrete. They seem cleaner and more aware, more themselves, as if both more spontaneous and more deliberate, more dream-like and more exquisitely observed, more creative and more obedient to nature. Recognizably what Raffael’s art has always been, they seem suddenly new.

It is as if Raffael’s art has achieved a refinement and clarification, a maturation, and what we thought we knew, surprisingly, we can now come to know. And yet, we should not be surprised, because there is an aspect of inevitability to this latest work, as there always is with the fulfillment phase of a master—even when the ultimate distillation of the work takes a seemingly unpredictable turn, in retrospect the line of development is clear. This is the work towards which Raffael’s career has been heading, and it is a culmination and a ratification of his place in contemporary art history. From the time Raffael began with his white-ground paintings of the mid-1960s—fragmentary images drawn from advertising and popular culture, painted against a pure white background—he has been categorized as a realist. Yet, by the mid-1970s, when Raffael turned to painting directly from nature, it became evident that he stood apart from the various modalities of realism that have dominated the last several decades. He is not and has not been a Photorealist, or a Neo-Expressionist, or, of course, a Pop artist. Unlike the other realist painters of our time, Raffael does not distort reality for emotional expressiveness or render photographically precise images with a stunning but arid and static precision of observation. What Raffael has retained and nurtured in his work, exclusively among the major realist painters of our time, is the aesthetic emotion—the love of paint as a method of vision, the palpably created vision that seeks the unfiltered truth of observation. In short, Raffael, alone among his peers, has retained the love of and devotion to beauty, or, to say the same thing in other words, his art has never lost its connection to life, to the vivacity of the image, to the sheer zest and urgency of animated nature, and of painting, of art, itself.

His is the dedication and the mark of an isolated soul—an individual’s devotion, a sole visionary’s occupation. And that is part of its inevitability. Raffael has always been one alone, an artist who has relied on and trusted his own inner impulses rather than followed the recipes for success in the art industry. He has sought to be an authentic artist, not an art star. In the mid-1980s, he departed the New York art world and moved to France, where he could pursue his art without distraction. There, he has stripped the inessentials from his life—he lives to paint and does nothing professionally but paint. He practices a commitment rather than a career, and so the circle of inevitability closes itself, and it makes full sense that his art would be among the rare few to reach the final stage of completion, the ultimate development of a full maturation.

What we discover in the paintings in the current exhibition is the thing itself—not just examples of Raffael’s art but his art per se, his art in its ideal form, his vision rendered and sublimated to the point that it instructs us in the very nature of art. Every work proves by its own example what art can do, what art is for. And more, these paintings reveal the intrinsic nature of the art that Raffael has made his own—the art of beauty. As one walks among these creations, one can virtually feel the anatomy of their intangible sensibility. One can begin to catalogue the qualities and the effects of pure beauty, and start to comprehend the purpose to which they aspire.

The translucency of the visual textures: Raffael’s paintings bring a gentle, almost immaterial touch to the eye, a contact as light as a breath, a visual impression that caresses with a delicacy beyond physical sensation. His images seem to hang before the paper, almost in layers, like leaves of some transcendental gelatin preparing to lift, slowing disclosing the light from behind. In paintings such as Re-Entry, 2003,

the watercolor is like a scrim, like stained glass somehow rendered on the opacity of the paper, dappling the surface with Raffael’s nearly abstract lozenges of color, which appear to be the prismatic facets of a jewel, a gem-like constellation of the spectrum of the imagination. There is something substantial and yet insubstantial about the vision. As you look, you feel as if you can fall into the image—gently, into a pillowed depth, as one might fall in love.

The suffusion of the color: Despite the gentle, almost ephemeral quality of the colors, they become an embracing environment of awareness, a manner of dreaming itself—a form of understanding and of inhabiting what one understands. As one gazes, one lives the colors, as if each were a distinct mood, a quality of reception into the mind. For the painting Pond for F. Garcia Lorca, 2005

POND FOR F. GARCIA LORCA, 2005

watercolor on paper, 76 x 76 1/2 inches

Raffael concerned himself with a particular poem by Lorca: “Romance Sonambulo.” It begins with these lines: “Green, how I want you green. / Green wind. Green branches.” The painting is precisely that gesture of mind. It is nature exactly observed, yet the moment has been selected for its imaginative import. We see in the work a world of green—the green of the inner feelings, the green of projecting thoughts, the mood of the nature of green, found at the edge of a pond of rippling water, found and aestheticized into art.

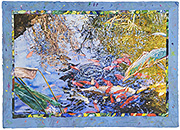

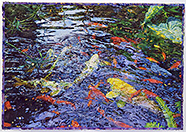

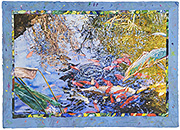

The bristling urge of the gesture: Focus on the elements of the images, the objects of nature depicted in the paint, and one will find there is a slight shimmer to the edges of things, a rippling energy that crosses the surface of the paintings, merging and re-merging in a confluence of flows, like the surfaces of the ponds in

Pond for F. Garcia Lorca; Inman’s Sacred Pond, 2004;and Life Streams, 2004.

INMAN'S SACRED POND, 2004

watercolor on paper, 37 x 51 1/2 inches

LIFE STREAMS, 2004

watercolor on paper, 39 1/4 x 56 inches

There is a wavering, a trembling of soft pressures that moves along a continuous medium, like a skin so sensitive that the slightest touch of the eye sends soft shivers running through it. All that we see are living objects, and the surfaces of the works are as if a skin of life itself, holding a tension that is gentle and expectant, like a held breath, like an urge to joy, an elation that almost wants to burst forth—a joyfulness of pure beauty. Every image is an ineluctable urge—like a hand held forth that one could not have withheld.

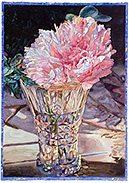

The condensation of the image: The image collects together, pulls itself into its form by a quality like an internal gravity, even as the specks of dappled color drift like specular motes. There has always been a formidable and enriching tension in Raffael’s paintings between the clarity of depicted nature and the visible assembly of patches of hue, as if realism and abstraction could readily co-exist. But here, in paintings such as

Homage to Carolyn Brady, 2005 (painted in honor of another wonderful painter, who died this year), Peony, 2004, and Roses for Vera, 2004,

HOMAGE TO CAROLYN BRADY - 1939-2005, 2005

watercolor on paper, 41 1/2 x 44 1/2 inches

PEONY, 2004

watercolor on paper, 36 1/2 x 26 inches

ROSES FOR VERA, 2004

watercolor on paper, 67 x 45 inches

both qualities have been intensified, and the rendered image takes on an appearance of solidity beyond what the artist has given us before. Each of these flower images has the felt density of a sculpture; each is so concretely evident that it might have been cut from stone. In every case, in all the new works, the image is like a precipitate, like a condensation, congealing like droplets of water collecting on leaves, on the scales of a fish surfacing, beading like pools of watercolor airing themselves to dry into art, like thought pulling together into moments of inspiration, like moments of inspiration densifying into fleeting insights, eternally remembered and impossible to explain.

The labyrinth of the image: Perhaps so clear in no work as in Homage to Carolyn Brady,

the image that seems to have formulated itself as much as it has been formulated by Raffael condenses into something utterly simple and utterly complex. It seems something of a maze, something of a centered pattern that swirls outward, that opens and unfolds, revealing a hard and delicate exactitude of imagined sight so clear, of such glistening and intense perception, that it mystifies. Which is to say that each painting is something of a mandala, something of a center of aesthetic contemplation, drawing the viewer’s eye into it even as it unfurls to disclose itself. And this is true regardless of the depicted image—it is as true of the spray of uncountable blossoms in

Eternal Return: Spring, 2004,

ETERNAL RETURN: Spring 2004

watercolor on paper, 61 1/2 x 45 inches

as it is of the single flower of Homage to Carolyn Brady. For there is no one center to any of the Raffael’s works, and not merely because every moment of each of them is rendered with equal precision, with equal attention beckoned of the eye. Rather, it is due the integration of the image—as with any work of art of the highest order, every aspect necessitates every other, every point on the surface is the point the entire work composes itself around, every moment in the work is the center. And this quality points toward the final attribute.

The inimitable image: There is a summary quality of impeccability to each work, an inimitability to every image. There is something iconic, and more than iconic, to Raffael’s images—they seem inevitable, indelible, and thus intrinsically immemorial. They are what we would like to call perfect. There is a palpable sense that each work is precisely right—that everything is where it must be, that amidst the wealth of detail Raffael renders, nothing is missing and nothing is superfluous. This is the supreme accomplishment for a work of art, and yet there is something distinctive in Raffael’s manner of the achievement: the inimitability of the image is not merely the result of proper composition. The paintings are composed masterfully, but they are not the product only of correct artificiality—they are also natural. The image is to be found in nature, just as we see it—or certainly we are convinced that we might as easily come upon it in nature as we have in a painting. And thus, the impeccability of the image is a found thing, something that can be located beyond the mind. The flawlessness of the image is not devised, but discovered. Inimitability is something obtained in the world.

These qualities are what Raffael shows us as the components of beauty, but they are not formulae for the formulation of beauty, they are not tricks of the trade—one can attempt every one of these effects and produce an inert, uninspired composition. The only formula is to be inspired—to know how to paint, how to see, how to feel. Beauty arises whole, of its own, and it comes only to those, such as Raffael, who can feel their way toward it, who can urge it to them by their passion for it. Beauty is a thing unto itself, and these are the influences of beauty. They are the concrete attributes of the marvelous, the prismatic aspects of its heat along the skin of the imagination, the intimate intricacies of the spell it casts.

And that spell, conjured as purely as Raffael now achieves it, reveals the purposes beauty serves, shows us what beauty does to us, and for us. The insight is divulged by the qualities of the image that stands like a veil toward which we are drawn, that vibrates with an energy unfolding like a rose to meet us coming to it, that forms a labyrinth centered on a secluded core, and that possesses an inimitability rooted both in the aesthetic imagination and in nature. Beauty is not a creation or a cast of mind; it is an apperception—it discloses a truth, it marks and invokes a deepened understanding, a knowledge of what can be known only through art, that has no words to convey it. Beauty is a vision of what lies behind the veil of appearances and yet is woven into the veil, distilled into the nature that lies all around us. Raffael has observed that “the act of painting is an act of nature,” and with the recognition that the distinction between the artificial and the natural, between what we do and what we find in the world, is itself artificial—for we ourselves are portions of nature—our divorce from the world is dissolved. What we seek finds us; what we move toward approaches us; what we explore opens itself to us. This is the truth of realism, a truth that can be told only by a supreme artist of the realistic: that the imagination and life are alike, and that to create from life is to return to life, to join life and the mind in a fusion that was always there.

Clearly, all art discovers what is within us, for all art is imagined, and there is a perennial question that nags the artistic enterprise: whether what is within us is the same as what is without us, whether the world and the mind respond to each other because they are identical. Does art unveil something beyond the limits of the imagination? The evidence of Raffael’s paintings is that it does, that what is within us is an extension of what is outside us, for in looking to the natural world, he has found the heart of his imagination, and in creating out of his artistic nature, he has located what is in the nature within which we live. Raffael’s explorations of the world are explorations of his self, but not the self we believe ourselves to be. Rather, he has located a larger Self, a Self that participates in, that is natural to, a larger world, a world beyond evident nature as it is beyond our assumed selves. “The Self is above and beyond who and what we believe we are. This act of painting is to help make that invisible visible.” And the larger Self is the soul that such poets as Rumi have told us come from elsewhere. Where it comes from, where it lives, is a larger reality, an invisible realm, a realm beyond the normal senses, the senses of all perhaps but a master artist.

There is a writer who once observed, as many have, that there are two kinds of people in the world—he divided them into those who believe there is treasure in the field and those who do not. So too, there are only two kinds of artists, and there are only two kinds of art lovers. Either one believes what we see here, what Raffael shows us, or one does not. And yet, there is no need of belief, for there is evidence, and the evidence is the beauty of his work. It is the tangible product of an art of exploration, the palpable result of discovery. There is no denying the overwhelming sensation of Raffael’s art, the visual effect that goes beyond all the specifiable visual attributes of his images—the breathtaking mood that leaves us speechless. That sensation is real, and it must be accounted for. It is the precipitate of the fully developed artistic journey, the physical distillation of his spiritual expedition, the evidence that has been returned from wither the artist goes—the thing itself, as it were, brought back alive.

In the art world, we live in a time of spiritual famine, a time in which the belief in the treasure, in the authenticity, in the truthfulness of the aesthetic vision has been lost. Here is Raffael’s proper place in art history: he has retained and nurtured his belief, he has kept the artistic faith, the faith that there is more than treasure, that there is wonder and awe and, better still, that there is the aesthetic quality, that the universe itself is a work of art, musical and magical—that the universe is a song. To realize this and to display it is to accomplish the kind of art one creates when one has made one’s way home, when one has achieved a fully flowered artistic maturity. It is to show us what was always there for us to understand, to show us the art in nature and the nature of art, such that, as T. S. Eliot wrote in “The Four Quartets,” we may “arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” It is to make what we know renewed.

©Mark Daniel Cohen, 2005

Complete and unedited version of Mark Daniel Cohen Essay

for Joseph Raffael/Nancy Hoffman Gallery Catalogue 2005.

and I intend to end up there.

—Rumi, “Who Says Words With My Mouth?”

Trans: Coleman Barks

There is something becomes of master artists as they progress. Throughout the history of the arts, throughout all the major art forms, we find artists who enter a stage of their work in which a change comes over the art they have devoted decades to making their own. Something new arises—often something utterly unpredictable, as often a further progression of the course they have been taking all along—but it is always a change that seems astonishing. And it is always a change that seems the fulfillment of a promise, as if after the long years of perfecting a style, a more perfect approach to art makes itself evident.

We see it rarely and only in the masters of the mode. We have found such changes of manner, such renewals of perfection, in the last sculpture of Michelangelo, in which he moved to incomplete figures embodying gestures of articulated ardency; in the poet W. B. Yeats, who evolved to a hard, seemingly granite emotionality bereft of all easy sentimentality; in Shakespeare, who found in “The Tempest” a profound ease that follows the composition of the most harrowing tragedies in our literature. We have seen such transformation in Mozart’s late, dark symphonies, in Titian’s last forms dissolving in the maelstrom of his brushstrokes, and in T. S. Eliot’s final turning toward mysticism. There seems to come to some artists an ultimate revelation, a distillation of the artistic vision, a rinsing of the eye of the creator, as if finally the long years of mastery turned out to be an apprenticeship and the truth of the art comes to bloom like a late-summer flower. The blossoming of that rose brings to us a realization that is indispensable: the art that had required so many years to reach its zenith becomes purified, relieved of all extrinsic matters, delivered of all infiltrates, of all peripheral concerns and superfluous habits of imagination and vision, and there is disclosed to us a purged, cleansed, unencumbered art, an art that seems as if the first art—there is revealed to us what art truly is.

Such moments in the chronology of a profound creativity force a question: “What art does one create when one has finally made one’s way home?” The evidence of these works makes clear that there are works of art and a sense of art that can come in the second half of an artistic career and that can be achieved by no other means. These are the works of maturity, the works of hard-won ability. In a time of general, culture-wide, even world-wide fascination with youth, there is a lesson here that we should acknowledge: we should turn the greater part of our attention from innovation to experience, for there is a vision that arrives in each field of creative endeavor only, and only occasionally, to the master artists of the mode.

Joseph Raffael is a master of such caliber—for more years now than anyone has an excuse to fail to recognize, he has been the most accomplished watercolorist in the contemporary art world—and the works in his current exhibition constitute a modern instance of this ultimate insight, of the renewal of the delving power of creation, of something thought perfect perfecting itself. His subject matter remains what it has been for many years—garden scenes and forest settings, flowers flourishing in the wild and settled in vases, ponds with fish drifting just below the surface, the play and lacing movements of water, birds blending in among the leaves. Yet there is something tangibly different, something fresh and distinct. These current works appear denser, more precise, more fully conceived, realized, and concrete. They seem cleaner and more aware, more themselves, as if both more spontaneous and more deliberate, more dream-like and more exquisitely observed, more creative and more obedient to nature. Recognizably what Raffael’s art has always been, they seem suddenly new.

It is as if Raffael’s art has achieved a refinement and clarification, a maturation, and what we thought we knew, surprisingly, we can now come to know. And yet, we should not be surprised, because there is an aspect of inevitability to this latest work, as there always is with the fulfillment phase of a master—even when the ultimate distillation of the work takes a seemingly unpredictable turn, in retrospect the line of development is clear. This is the work towards which Raffael’s career has been heading, and it is a culmination and a ratification of his place in contemporary art history. From the time Raffael began with his white-ground paintings of the mid-1960s—fragmentary images drawn from advertising and popular culture, painted against a pure white background—he has been categorized as a realist. Yet, by the mid-1970s, when Raffael turned to painting directly from nature, it became evident that he stood apart from the various modalities of realism that have dominated the last several decades. He is not and has not been a Photorealist, or a Neo-Expressionist, or, of course, a Pop artist. Unlike the other realist painters of our time, Raffael does not distort reality for emotional expressiveness or render photographically precise images with a stunning but arid and static precision of observation. What Raffael has retained and nurtured in his work, exclusively among the major realist painters of our time, is the aesthetic emotion—the love of paint as a method of vision, the palpably created vision that seeks the unfiltered truth of observation. In short, Raffael, alone among his peers, has retained the love of and devotion to beauty, or, to say the same thing in other words, his art has never lost its connection to life, to the vivacity of the image, to the sheer zest and urgency of animated nature, and of painting, of art, itself.

His is the dedication and the mark of an isolated soul—an individual’s devotion, a sole visionary’s occupation. And that is part of its inevitability. Raffael has always been one alone, an artist who has relied on and trusted his own inner impulses rather than followed the recipes for success in the art industry. He has sought to be an authentic artist, not an art star. In the mid-1980s, he departed the New York art world and moved to France, where he could pursue his art without distraction. There, he has stripped the inessentials from his life—he lives to paint and does nothing professionally but paint. He practices a commitment rather than a career, and so the circle of inevitability closes itself, and it makes full sense that his art would be among the rare few to reach the final stage of completion, the ultimate development of a full maturation.

What we discover in the paintings in the current exhibition is the thing itself—not just examples of Raffael’s art but his art per se, his art in its ideal form, his vision rendered and sublimated to the point that it instructs us in the very nature of art. Every work proves by its own example what art can do, what art is for. And more, these paintings reveal the intrinsic nature of the art that Raffael has made his own—the art of beauty. As one walks among these creations, one can virtually feel the anatomy of their intangible sensibility. One can begin to catalogue the qualities and the effects of pure beauty, and start to comprehend the purpose to which they aspire.

The translucency of the visual textures: Raffael’s paintings bring a gentle, almost immaterial touch to the eye, a contact as light as a breath, a visual impression that caresses with a delicacy beyond physical sensation. His images seem to hang before the paper, almost in layers, like leaves of some transcendental gelatin preparing to lift, slowing disclosing the light from behind. In paintings such as Re-Entry, 2003,

the watercolor is like a scrim, like stained glass somehow rendered on the opacity of the paper, dappling the surface with Raffael’s nearly abstract lozenges of color, which appear to be the prismatic facets of a jewel, a gem-like constellation of the spectrum of the imagination. There is something substantial and yet insubstantial about the vision. As you look, you feel as if you can fall into the image—gently, into a pillowed depth, as one might fall in love.

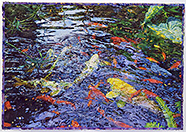

The suffusion of the color: Despite the gentle, almost ephemeral quality of the colors, they become an embracing environment of awareness, a manner of dreaming itself—a form of understanding and of inhabiting what one understands. As one gazes, one lives the colors, as if each were a distinct mood, a quality of reception into the mind. For the painting Pond for F. Garcia Lorca, 2005

POND FOR F. GARCIA LORCA, 2005

watercolor on paper, 76 x 76 1/2 inches

Raffael concerned himself with a particular poem by Lorca: “Romance Sonambulo.” It begins with these lines: “Green, how I want you green. / Green wind. Green branches.” The painting is precisely that gesture of mind. It is nature exactly observed, yet the moment has been selected for its imaginative import. We see in the work a world of green—the green of the inner feelings, the green of projecting thoughts, the mood of the nature of green, found at the edge of a pond of rippling water, found and aestheticized into art.

The bristling urge of the gesture: Focus on the elements of the images, the objects of nature depicted in the paint, and one will find there is a slight shimmer to the edges of things, a rippling energy that crosses the surface of the paintings, merging and re-merging in a confluence of flows, like the surfaces of the ponds in

Pond for F. Garcia Lorca; Inman’s Sacred Pond, 2004;and Life Streams, 2004.

INMAN'S SACRED POND, 2004

watercolor on paper, 37 x 51 1/2 inches

LIFE STREAMS, 2004

watercolor on paper, 39 1/4 x 56 inches

There is a wavering, a trembling of soft pressures that moves along a continuous medium, like a skin so sensitive that the slightest touch of the eye sends soft shivers running through it. All that we see are living objects, and the surfaces of the works are as if a skin of life itself, holding a tension that is gentle and expectant, like a held breath, like an urge to joy, an elation that almost wants to burst forth—a joyfulness of pure beauty. Every image is an ineluctable urge—like a hand held forth that one could not have withheld.

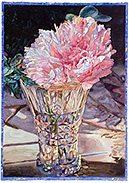

The condensation of the image: The image collects together, pulls itself into its form by a quality like an internal gravity, even as the specks of dappled color drift like specular motes. There has always been a formidable and enriching tension in Raffael’s paintings between the clarity of depicted nature and the visible assembly of patches of hue, as if realism and abstraction could readily co-exist. But here, in paintings such as

Homage to Carolyn Brady, 2005 (painted in honor of another wonderful painter, who died this year), Peony, 2004, and Roses for Vera, 2004,

HOMAGE TO CAROLYN BRADY - 1939-2005, 2005

watercolor on paper, 41 1/2 x 44 1/2 inches

PEONY, 2004

watercolor on paper, 36 1/2 x 26 inches

ROSES FOR VERA, 2004

watercolor on paper, 67 x 45 inches

both qualities have been intensified, and the rendered image takes on an appearance of solidity beyond what the artist has given us before. Each of these flower images has the felt density of a sculpture; each is so concretely evident that it might have been cut from stone. In every case, in all the new works, the image is like a precipitate, like a condensation, congealing like droplets of water collecting on leaves, on the scales of a fish surfacing, beading like pools of watercolor airing themselves to dry into art, like thought pulling together into moments of inspiration, like moments of inspiration densifying into fleeting insights, eternally remembered and impossible to explain.

The labyrinth of the image: Perhaps so clear in no work as in Homage to Carolyn Brady,

the image that seems to have formulated itself as much as it has been formulated by Raffael condenses into something utterly simple and utterly complex. It seems something of a maze, something of a centered pattern that swirls outward, that opens and unfolds, revealing a hard and delicate exactitude of imagined sight so clear, of such glistening and intense perception, that it mystifies. Which is to say that each painting is something of a mandala, something of a center of aesthetic contemplation, drawing the viewer’s eye into it even as it unfurls to disclose itself. And this is true regardless of the depicted image—it is as true of the spray of uncountable blossoms in

Eternal Return: Spring, 2004,

ETERNAL RETURN: Spring 2004

watercolor on paper, 61 1/2 x 45 inches

as it is of the single flower of Homage to Carolyn Brady. For there is no one center to any of the Raffael’s works, and not merely because every moment of each of them is rendered with equal precision, with equal attention beckoned of the eye. Rather, it is due the integration of the image—as with any work of art of the highest order, every aspect necessitates every other, every point on the surface is the point the entire work composes itself around, every moment in the work is the center. And this quality points toward the final attribute.

The inimitable image: There is a summary quality of impeccability to each work, an inimitability to every image. There is something iconic, and more than iconic, to Raffael’s images—they seem inevitable, indelible, and thus intrinsically immemorial. They are what we would like to call perfect. There is a palpable sense that each work is precisely right—that everything is where it must be, that amidst the wealth of detail Raffael renders, nothing is missing and nothing is superfluous. This is the supreme accomplishment for a work of art, and yet there is something distinctive in Raffael’s manner of the achievement: the inimitability of the image is not merely the result of proper composition. The paintings are composed masterfully, but they are not the product only of correct artificiality—they are also natural. The image is to be found in nature, just as we see it—or certainly we are convinced that we might as easily come upon it in nature as we have in a painting. And thus, the impeccability of the image is a found thing, something that can be located beyond the mind. The flawlessness of the image is not devised, but discovered. Inimitability is something obtained in the world.

These qualities are what Raffael shows us as the components of beauty, but they are not formulae for the formulation of beauty, they are not tricks of the trade—one can attempt every one of these effects and produce an inert, uninspired composition. The only formula is to be inspired—to know how to paint, how to see, how to feel. Beauty arises whole, of its own, and it comes only to those, such as Raffael, who can feel their way toward it, who can urge it to them by their passion for it. Beauty is a thing unto itself, and these are the influences of beauty. They are the concrete attributes of the marvelous, the prismatic aspects of its heat along the skin of the imagination, the intimate intricacies of the spell it casts.

And that spell, conjured as purely as Raffael now achieves it, reveals the purposes beauty serves, shows us what beauty does to us, and for us. The insight is divulged by the qualities of the image that stands like a veil toward which we are drawn, that vibrates with an energy unfolding like a rose to meet us coming to it, that forms a labyrinth centered on a secluded core, and that possesses an inimitability rooted both in the aesthetic imagination and in nature. Beauty is not a creation or a cast of mind; it is an apperception—it discloses a truth, it marks and invokes a deepened understanding, a knowledge of what can be known only through art, that has no words to convey it. Beauty is a vision of what lies behind the veil of appearances and yet is woven into the veil, distilled into the nature that lies all around us. Raffael has observed that “the act of painting is an act of nature,” and with the recognition that the distinction between the artificial and the natural, between what we do and what we find in the world, is itself artificial—for we ourselves are portions of nature—our divorce from the world is dissolved. What we seek finds us; what we move toward approaches us; what we explore opens itself to us. This is the truth of realism, a truth that can be told only by a supreme artist of the realistic: that the imagination and life are alike, and that to create from life is to return to life, to join life and the mind in a fusion that was always there.

Clearly, all art discovers what is within us, for all art is imagined, and there is a perennial question that nags the artistic enterprise: whether what is within us is the same as what is without us, whether the world and the mind respond to each other because they are identical. Does art unveil something beyond the limits of the imagination? The evidence of Raffael’s paintings is that it does, that what is within us is an extension of what is outside us, for in looking to the natural world, he has found the heart of his imagination, and in creating out of his artistic nature, he has located what is in the nature within which we live. Raffael’s explorations of the world are explorations of his self, but not the self we believe ourselves to be. Rather, he has located a larger Self, a Self that participates in, that is natural to, a larger world, a world beyond evident nature as it is beyond our assumed selves. “The Self is above and beyond who and what we believe we are. This act of painting is to help make that invisible visible.” And the larger Self is the soul that such poets as Rumi have told us come from elsewhere. Where it comes from, where it lives, is a larger reality, an invisible realm, a realm beyond the normal senses, the senses of all perhaps but a master artist.

There is a writer who once observed, as many have, that there are two kinds of people in the world—he divided them into those who believe there is treasure in the field and those who do not. So too, there are only two kinds of artists, and there are only two kinds of art lovers. Either one believes what we see here, what Raffael shows us, or one does not. And yet, there is no need of belief, for there is evidence, and the evidence is the beauty of his work. It is the tangible product of an art of exploration, the palpable result of discovery. There is no denying the overwhelming sensation of Raffael’s art, the visual effect that goes beyond all the specifiable visual attributes of his images—the breathtaking mood that leaves us speechless. That sensation is real, and it must be accounted for. It is the precipitate of the fully developed artistic journey, the physical distillation of his spiritual expedition, the evidence that has been returned from wither the artist goes—the thing itself, as it were, brought back alive.

In the art world, we live in a time of spiritual famine, a time in which the belief in the treasure, in the authenticity, in the truthfulness of the aesthetic vision has been lost. Here is Raffael’s proper place in art history: he has retained and nurtured his belief, he has kept the artistic faith, the faith that there is more than treasure, that there is wonder and awe and, better still, that there is the aesthetic quality, that the universe itself is a work of art, musical and magical—that the universe is a song. To realize this and to display it is to accomplish the kind of art one creates when one has made one’s way home, when one has achieved a fully flowered artistic maturity. It is to show us what was always there for us to understand, to show us the art in nature and the nature of art, such that, as T. S. Eliot wrote in “The Four Quartets,” we may “arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” It is to make what we know renewed.

©Mark Daniel Cohen, 2005

Complete and unedited version of Mark Daniel Cohen Essay

for Joseph Raffael/Nancy Hoffman Gallery Catalogue 2005.