The idea that a painting could contain deeply hidden expressions

came to me in the Berkeley Art Museum in the summer of 1993,

on a pounding day when I had retreated into the museum to escape

the crowd and the noise and the heat.

Overloaded by the incessant

stimuli that I have never learned to shut out, I moved from painting

to painting, looking for some image in which I could take refuge.

It is one of the ways I try to deal with sensory overload --

seeking a single thing that absorbs my total attention,

so that

I forget everything that is overwhelming me from outside and

inside, and focus.

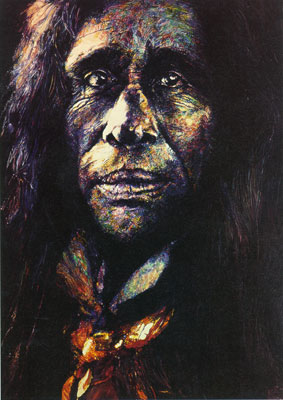

When I reached Joseph Raffael's

painting of a Pomo Indian, my confusion stopped, and I left my

overloaded, busy, noisy, stressful world and entered the world

of the painting.

It is a nighttime portrait -- a dark, almost black-and-white

work with a face suggested by myriad reflections, rather than

by the usual sense of outline and mass.

As I entered the painting,

I slowly became aware that I was seeing a face, insofar as it

could be seen, by reflection from an unseen fire below and unseen

stars above,

and perhaps the light (from the upper left) from

the sliver of a moon. To see the face at all is to intuit that

it is the face of a man alone, under the stars, in the desert,

over a dying fire.

The Pomo's face seemed to come to rest amid thousands of splinters

of light and darkness, in a symphony of sadness. It told of loss,

defeat, rejection,

of a way of life torn off, crumpled up, thrown

into the fire, and burning in its last ashes.

It told of the

frail thread that held the sure skills of the warrior, alone

in the vast Southwestern desert night, to his uselessness in

a world that had changed,

a world that did not need his knowledge,

a world that considered him at best irrelevant.

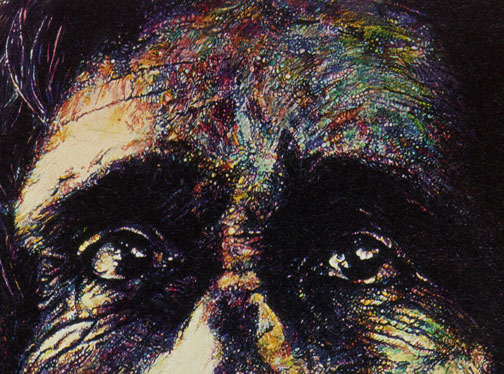

As the Pomo's eyes looked straight into me across the unseen

firelight, penetrating the deep desert darkness that seemed to

open up through the painting, like a window, his expression held

me with what seemed to be its awareness of its own condition.

He gradually took on the tragic dignity of those who lose everything

except awareness.

Then the expression on the Pomo's face modulated into something

that almost shocked me: His sadness was not for himself alone.

It was not only a sadness for his people, his way of life. He,

stripped of everything, alone in the huge and merciless desert,

in the dying firelight, under the undying stars, was feeling

sorry for me!

He -- brushed aside, invalidated by history,

relegated to irrelevance -- was looking at me as someone who

had not yet discovered the same things about myself, but sooner

or later would -- as everyone everywhere will eventually feel

the seeming solidity of their world dissolve into something even

more insubstantial than scattered reflections from firelight

and starlight in the desert darkness.

Then, perhaps 20 minutes into the painting, alone in this

corner of the gallery, I experienced one of the most remarkable

things I have ever seen.

All of a sudden, unrelated to anything

I had been seeing or thinking or feeling up to now, an entirely

different expression emerged from the flickering sadness of the

Pomo's face. "Emerged" is too slow a word. It was as

if the image suddenly leapt about 18 inches off the canvas and

stood planted there in three dimensional space.

The effect was similar to that of looking at one of those

computer-generated images that looks like a jumbled pattern until

your eyes find the right focus -- and at that point a three-dimensional

image leaps off the page at you with startling clarity.

The new face of the Pomo was still the face I had been seeing

as in an inexpressible pain over the loss of his world.

Only

it had been transformed, as if purified beyond all pain by a

radiant gladness that was not on the face but inside it, shining

through -- inside the night, shining through,

inside the firelight

and starlight, radiating through everything -- a great, glad,

peaceful, endlessly creative, undying light that he knew himself

to be part of and that, all along,

he had been trying to lead

me to see.

I

stood there, the two of us alone in a gallery,

tears streaming down my face,

while the Pomo that I had been feeling

sorry for, gave me his blessing.

Gerald Grow

Professor of Journalism

Florida A&M University

©Gerald Grow

This essay is reprinted with permission of the author.