"He is great

who is what he is from Nature, and who never reminds us of others."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Joseph Raffael's romantic journey pauses ever so briefly to share what

has been revealed-revelations so beautiful

that we quickly send him on his

way to discover more.

Cezanne and generations of painters before him knew that ultimately

nature stands as the greatest of teachers.

Joseph Raffael's homage to natural

form and clear dedication to timeless notions of beauty remain his strength.

Aesthetic issues have some how been abandoned in recent years by

numerous artists whom I believe are humbled by historical achievements.

Raffael

on the other hand appears to revel in the challenge.

His is an art of

honest and passionate exploration.

In both concept as well as technical

execution, his reach is toward that universal manifestation of beauty

which

Santayana has called an "expression of the ideal ... the finest flower of human nature."

The paintings of Joseph Raffael are a clear reminder of what

it is about art that we hold dear.

The artist's interest in Eastern thought is not surprising given his steadfast devotion to the concept of a true human partnership

with and interconnectedness to all living beings.

His paintings have long

celebrated the miracle and mystery of life and the environments which sustain it.

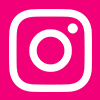

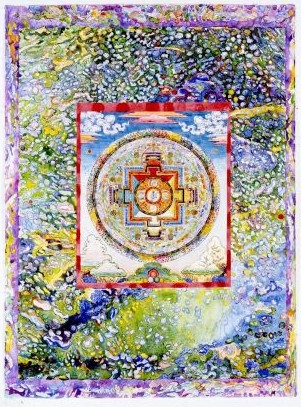

However his incorporation of Tibetan Buddhist imagery in the work

serves to accentuate the significance of the tanka intellectually as well as

visually.

But on a strictly formal level the inclusion of the tankas in such

works as Illuminations

Spring and Illuminations Summer makes for extraordinarily complex visual poetry.

In juxtaposing the tankas over a hand colored lithograph created over 20 years ago and then restating

the

combinations in watercolor, he has created offspring of an entirely different

personality.

The intrinsic symmetry of the Buddhist pieces placed dead center on the organic field of water and marine life produces a sense of unity

which

on a purely visual level is not as easily accomplished as it appears.

The artist's reliance upon intuition and experience make it work.

Interestingly, Western art from the golden mean onward has discouraged the centrally oriented composition.

Virtually all of the works in this exhibition

adhere to the tanka's central focus, a perceptual blending of east and west

independent of the more obvious symbolic or conceptual mixing of

cultures.

We must also recall that Joseph Albers was an early influence making the centering of imagery

a not so unconventional approach in paying "homage

to the square."

Illuminations- Spring

watercolor on paper

60 x 44 1/2 in.

152.4 x 113 cm

2000

Illuminations- Summer

watercolor on paper

60 1/4 x 44 1/2 in.

153 x 113 cm

2000

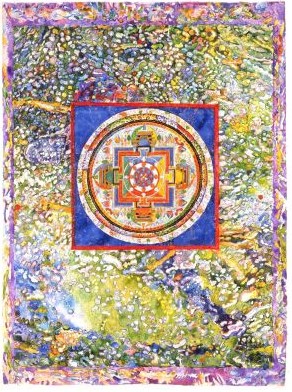

Vincent Van Gogh's generation of

painters was also drawn to a strong non-western influence, the Japanese print.

The effect of Japanese art on these earliest of modem painters is well known, but the influence of Japanese culture moved well beyond its known impact on pictorial space.

Van Gogh for one was truly taken by the non-western perspective on daily

life.

"Come now, isn't it almost a true religion which these simple Japanese

teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers?" (Letter

to Theo-Sept. 1888.)

It is no wonder that Vincent Van Gogh, his life and

his art, have meant so much to Joseph Raffael.

In View, a self

portrait by

Van Gogh is superimposed over Tibetan imagery.

It is Van Gogh's suffering

and his response to it which has especially touched Raffael.

Suffering

exists as one of the four noble truths of Buddhism and is, in the words of the

artist,

"what we share as humans."

View

watercolor and acrylic on paper

53 x 44 1/2 in.

134.6 x 113 cm

2000

And just as Van Gogh was impressed by the Japanese artist's need "to

live in nature" and to study a single blade of grass

and its ultimate

relationship to all of nature, so too has Joseph Raffael absorbed the non-western

point

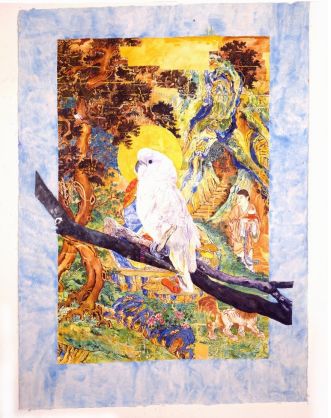

of view of the interconnectedness of all life forms. In Harvest Moon a

pet cockatoo (Joseph and Lannis Raffael maintain an aviary of pet birds)

is painted on an orange tree branch with an oriental landscape and a freely brushed border serving as a ground.

Spatially this work is

extraordinarily complex. In it the most prominent shape, the white bird, rests on a

branch

that transverses the landscape, which very typically portrays an

oriental flatness.

Add to the mix the blue sky-like border, which even without consideration of the dynamics of color within the Buddhist piece,

offers us a breathtakingly beautiful ambiguity.

Harvest Moon

watercolor on paper

44 1/2 x 62 in.

113 x 157.5 cm

2000

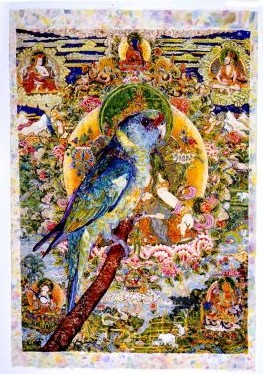

Although part of the same series,Bird

and Tanka is distinctive in the manner by which the Tibetan tanka integrates with the tropical bird representation.

At first glance, the piece resembles a Medieval

tapestry, an observation which Raffael welcomes.

It reveals what the artist calls "an interweaving of complexities" paralleling life itself as a tapestry in

which

"one event, one thought goes to another." Technically, the work is a

marvel.

The watercolor medium is shown to full advantage, as the tanka explodes before us in a full spray of color harnessed masterfully to define every

element of this enormously complex composition. The freely color washed border in one sense frames the work but in another possesses its own

dynamic

as we appear to experience a vaporization of the edge, an abstracted extension.

Bird and Tanka

watercolor on paper

63 1/2 x 44 1/2 in.

161.3 x 113 cm

2000

Photography has long been a valuable tool of Joseph Raffael, using it

as a point of departure and to assist in the early conceptualization phase

of the works.

In Millennium as in Bird &

Tanka, the bird is

photographed and its cut-out image is carefully placed on the tanka,

re-photographed as a

unit, and then re-interpreted in paint.

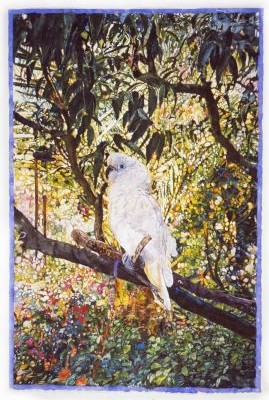

In Millennium, the

artist

pre-visualized a favorite white cockatoo on an orange branch in a lush environment of

plant life.

The photo montage affirmed his vision, which was a far more

logical juxtaposition than what occurs in Spring

Bridge.

In this work, a

Chinese fan is placed atop a sheet of scrap paper from the studio which had been

used by the artist to blot his brush.

What a truly arresting work results as the regularity of the fan shape, with its intricate classical oriental

decor, is

set against a purely improvised, spontaneously applied ground.

It

works, and works very well. Perhaps the artists comfort with such dissonant visual elements stems from his early works with abstract expressionist painter

James Brooks at Yale back in the 1950s. The spontaneity of the abstract expressionist method interested him then and perhaps

it can be said continues to reveal itself in more whispered tones.

But Spring Bridge demonstrates the amazing ability of Raffael to appropriate the

unexpected.

Millenium

watercolor on paper

45 x 67 1/2 in.

114.3 x 171.5 cm

2000

Spring

Bridge

watercolor on paper

44 1/2 x 65 1/2 in.

1992

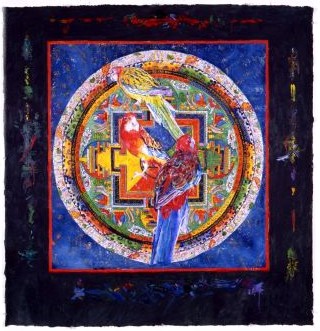

In Spirit in which three tropical birds harmonize through color and placement with the Tibetan circular from, the artist enriches the dark

green border with painterly markings.

The freely brushed acrylic presents a wonderful contrast to the finely tuned technique demonstrated within

the red square.

In both works two distinct sensibilities link effectively as

one.

Spirit

watercolor on paper

46 1/4 x 44 1/2 in.

117.5 x 113 cm

2000

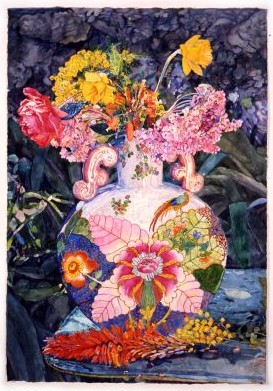

In Late Winter Bouquet and The Gift we see the artist returning to the familiar floral theme but with a wonderful freshness as if approaching

the subject for the very first time.

In Winter Light a Chinese vase picked

up at a flee market, with its stylized ceramic flower forms, hold fresh cut

garden flowers against shadowed foliage.

Nature has not given man a more

beautiful sight and Raffael manages, as no other artist before him, to extract

that beauty.

The device of the Chinese floral vase, the contrasting cold

metal table and the darkened organic ground conceptually and perceptually

are

a tribute to the universal and timeless allure of floral beauty.

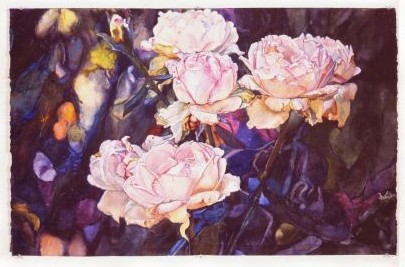

The Gift, roses given to Lannis Raffael, speak not only of the magnificence of the flower but also of the delicacy of nature

and the need for humankind to

see it as a gift to be cherished.

The Gift

watercolor on paper

26 x 40 3/4 in.

66 x 103.5 cm

2000

Late Winter Bouquet

watercolor on paper

64 1/2 x 44 1/2 in.

163.8 x 113 cm

2000

In Morning Bird Joseph Raffael returns to his signature theme of water

and does so in glorious fashion.

The dramatic horizontality of the work

adds to the serenity of this most beautiful of subjects.

So convincing is the portrayal that we expect to hear the chirping of the bird so gingerly perched on the lily pads.

Joseph Raffael is the master of this genre.

He supports a remarkable eye for the romantic in nature, with a level of

skill which is without peer.

Morning

Bird

watercolor

on paper

17 3/4 x 66 1/4 in.

45.1 x 168.3 cm

2000

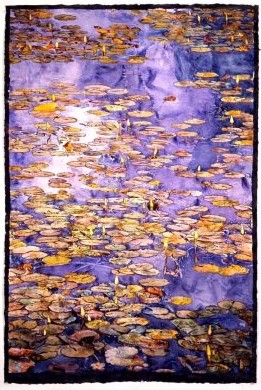

Morning at Kodai 2000 is at once an etherial abstraction and a wondrous document of natural phenomena.

In presenting and interpreting this particular slice of nature, the artist has chosen a perspective in

which the simplest of forms build toward a dramatic illusionary display.

Water

and sky are as one establishing a floating stage in which the plants move rhythmically away from the viewer.

Adding richly to this visual treat

is the sense of a gestalt in which the individual disk shaped lily pads

are

seen by the eye as individual elements and then as a unified whole.

This

"grouping" effect presents a tasty icing to an already visually luscious work.

Morning at Kodai

watercolor on paper

66 3/4 x 44 1/2 in.

169.5 x 113 cm

2000

Along the Way carries a baroque-like quality in which stunningly

beautiful flowering water plants appear to sway horizontally across the work.

As

in all of nature, what appears at first glance to be a sameness, is not at

all.

The artist has scrutinized each plant--honestly portraying its

individual characteristics and praising that uniqueness.

What a lesson we learn

daily along the way--if only we pause to notice and hopefully applaud what is found.

It is said that Beethoven spent as much time in nature as at the piano and that Einstein spent a lifetime trying to decipher the mystery

of its beauty.

The Bible certainly reminds us of Gods pleasure with what He brought forth. The artist's role is perhaps to remind us of that.

Along The Way

watercolor on paper

41 1/2 x 68 in.

105.4 x 172.7 cm

2000

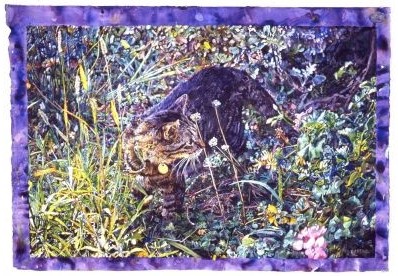

Raffael is dedicated to an imagery that first and foremost is most meaningful to him.

Tigre's

Spring recalls a favorite pet, painted in the twilight of his life within the environment which he loved.

This is obviously a very special portrait, a tribute to a treasured companion.

The form of the cat somewhat concealed by the brush and its natural

markings, emerges with the grace and nobility of a great jungle tiger.

Joseph Raffael's reverence for and admiration of all things living extends

also to the weeds.

This is not a generic ground cover but rather individual

plants carefully indicated and painted as if each were atrophied flower.

Tigre's Spring

watercolor on paper

41 3/4 x 60 3/4 in.

106 x 154.3 cm

2000

And while great art, the art which has endured through time, deals with eternal truths--it must also inspire on a perceptual level.

Joseph Raffael's art not only reflects the highest of human values, it also entertains us, in keeping with the greatest of artistic traditions.

For in the end what interests him most is the very act of applying paint to paper.

His paintings he says, are ultimately about painting. That's certainly enough for us.

Louis A. Zona Executive Director,

The Butler Institute of American Art

Professor of Art, Youngstown State University