One

recognizes in Joseph Raffael the mute poet’ of Horace’s “Ut pictura

poesis,” and it is from the navigation point of the ancient and

Renaissance lore of the painter/poet as seer that one locates the

essence and alignment of Raffael’s mind and artistic intent.

Concepts such as furor divinus, alta fantasia, intuition, visionary power, and transcendence are a vital, driving force for Raffael.

“Artists . . . have insights into the universal . . . They live in a mysterious place. . .Their will has nothing to do with it, and that is why making art is in a sense very religious”.

(Joseph Raffael, essay by Joyce Petschek, catalogue for the one man exhibition, Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York, 1990, p. 4.)

Artists often manifest their artistic drives in early childhood; in fact, for the Renaissance author of the Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari,

this was a sure sign of true vocation and greatness.

By the time Joseph Raffael was seven, drawing was his favorite pastime, and nature his closest friend. From 1951 - 56, he attended Cooper Union (BFA) and then Yale (MFA),

following a preferred route for talented young artists. It was the heyday of Abstract Expressionism and Raffael drew important lessons from that experience that continue to be operative for him - “let go”, trust the brush and the paint, ritualize the act of painting. Raffael's perhaps most respected teacher was Josef Albers, with whom he studied at Yale. Raffael was impressed with Albers, for one, because he insisted that his students not paint like him and, in fact, that they not paint in already established styles (for example, Abstract Expressionism). Albers also spoke not of hues and tones, but of feeling, weather, times of day. This meshed with Raffael’s own deep responses to, and regard for, the natural world.

After graduate school, Raffael joined the textile design studio of Jack Prince (which was also an important starting point for Carolyn Brady, Audrey Flack and other artists of that generation). Raffael recalls that in the Prince studio he learned the discipline of draftsmanship (providing the opportunity to exercise and strengthen his ability to draw), to work within the limits of a project, and to reproduce colors exactly. This experience, combined with a Fulbright to Italy, and the encounter with the 14th and 15th century Italian masters, began to shake loose the overarching appeal abstraction held for him. After some early experiments with figural subject matter, his mature pictorial vocabulary began to formulate.

For about a decade, he focused, among other things, on solitary images in monumental scale of heads of ancient statuary (Buddha), native American Indians, and animals, as a way of understanding the ancient view of the infinite and of the making of art as a product of a spiritual activity.

Trips to Asia, the challenging experiences of life threatening illnesses, death of close family members, the breakdown of a first marriage, the clatter of the commercial aspects of art all, ultimately, have driven him to the solace offered by the essence of Nature and to the paring down of his own psyche to its essential self.

And it is through his psyche that Joseph Raffael, the artist, moves from consciousness to a state of heightened subconscious awareness as he seeks to identify the essence of an object or of a state of being, and to make it tangible. He searches for imagery that will touch not only his but the viewers own subconscious as well, imagery that will stir the soul.

He seeks through his art to arouse recognition of the archetypal, of the divine, in the accidentals of the natural world.

His imagery, medium and technique work in concert and are tuned in this resolve - birds, flowers, landscape, color, light, and brushwork become the symbols of love, beauty, innocence, divine fragrance, peace, order, mystery, and the ephemeral.

Raffael has stated it most clearly. “Painting is the subject of my work, and nature the inspiration.” ("Interview with Joseph Raffael," Joseph Raffael: A Dream Remembered, Nancy Hoffman Gallery, catalogue for the exhibition, 1986, p. 6.)

Raffael’s imagery was more obviously stated in his early work, his symbolism more direct: for example, bird = spirit; a Japanese shrine in a winter landscape = serenity.

These more literal elements have given way in the later work to the physical dynamics of imaging (light, color, energy, quality of rendering), and to a new maturity of vision that underpins the image. In a number of earlier paintings, highly defined borders of abstract form and visionary color framed the central image (perhaps suggested, in part, by the work of his teacher Josef Albers), as if the picture were the meeting point of two different realities.

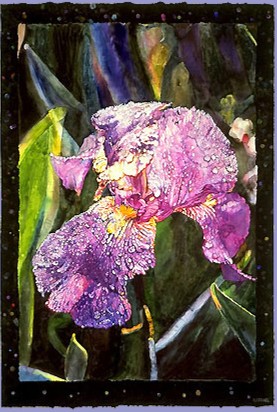

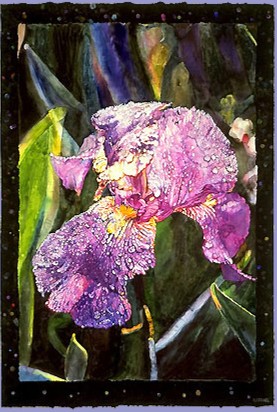

In such paintings as After the Rain, An Iris with Border (Seavest Collection), for example, these borders seem to have metamorphosed into the ephemeral backgrounds of his floral

and still life pictures, creating a more homogeneous tension between planes in and out of focus.

These backgrounds with a quality of light diffused as if through stained glass, identify a realm somewhere between the terrestrial and the celestial, between the tangible and the ideal. In these stunning images beauty and opulence unabashedly confront the viewer, and scale overwhelms. Composition, line, color, and brushwork have an emotional/spiritual pitch.

The image – whether of a flower resplendent in its full maturity, or of Lannis whose physicality is dissolved in the floral array of a favored dress,

or of koi stirring the surface of a pond (Before Solstice,Seavest Collection) - intoxicates.

Raffael’s work is not easily categorized, though associations with the Post Impressionists, Symbolists, Naturalists, Expressionists and even Photorealists have been offered.

To the point here, is the fact that Raffael does use photographs as an aid in the process of creating an image. But in distinction to other of his Realist colleagues who also employ photographs in their creative process, Raphael uses them as a vehicle of meditation, not so much as Photorealism than as a sort of Photo-transcendentalism.

In fact, for a very long time Raffael painted exclusively in the dark, with only a slide projected onto a small screen located next to the surface on which he was about to paint.

The solitary image lit brightly from behind has allowed him to extract the electric, prismatic effect of blues and reds, and to understand the advantage of enhanced luminosity.

It has contributed to the development of his special palette and versatile, expressive brushwork, which are ultimately in service to the description of the extraordinary colors, emanations and essence of Nature herself.

Raffael draws inspiration from another modern art form as well - cinema.

He is a great fan of the big screen, and seeks in the exploded, super scale and resonance of his own paintings to impart something of the impact and story line of movies in a single startling image.

As evidenced by the paintings by Raffael that illustrate this essay, the breakdown of the surfaces of objects seen at close range into a network of variously pitched and colored marks has the optical effect of scintillating energy.

This quality of imaging draws us from normal vision into our mind's eye, and seeks to convey non-verbal, mystical experiences with Nature.

Raffael works comfortably in acrylic, but tends to prefer watercolor.

Watercolor offers him a more direct echo of the unrepeatable and unpredictable events in nature, for example, the split second that light or rain momentarily transform a leaf or petal, or that just beneath the water’s surface koi,never touching, glide effortlessly past each other like molten gold.

While Raffael’s pictorial surface can at times be Impressionistic, at times Expressionistic, his artistic intent places him in the tradition - from antiquity to the Symbolists, to those similarly inspired 20th century masters - of artist as seer.

As such, his art might be viewed as transcending not only the material sphere but the temporal one as well,

offering a glimpse of the visionary in the often vacuous culture of the late 20th century

much as Blake, Redon or Kandinsky had sought to in their own troubled worlds.

©by Virginia Anne Bonito, "Get Real: Contemporary American Realism from the Seavest Collection" Raffael essay, DUMA, 1998, pp. 104 – 108; revised for the Seavest Collection Webpage and in-house Catalogue, May 2, 2000.

This essay is reprinted with permission of the author.

Concepts such as furor divinus, alta fantasia, intuition, visionary power, and transcendence are a vital, driving force for Raffael.

“Artists . . . have insights into the universal . . . They live in a mysterious place. . .Their will has nothing to do with it, and that is why making art is in a sense very religious”.

(Joseph Raffael, essay by Joyce Petschek, catalogue for the one man exhibition, Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York, 1990, p. 4.)

Artists often manifest their artistic drives in early childhood; in fact, for the Renaissance author of the Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari,

this was a sure sign of true vocation and greatness.

By the time Joseph Raffael was seven, drawing was his favorite pastime, and nature his closest friend. From 1951 - 56, he attended Cooper Union (BFA) and then Yale (MFA),

following a preferred route for talented young artists. It was the heyday of Abstract Expressionism and Raffael drew important lessons from that experience that continue to be operative for him - “let go”, trust the brush and the paint, ritualize the act of painting. Raffael's perhaps most respected teacher was Josef Albers, with whom he studied at Yale. Raffael was impressed with Albers, for one, because he insisted that his students not paint like him and, in fact, that they not paint in already established styles (for example, Abstract Expressionism). Albers also spoke not of hues and tones, but of feeling, weather, times of day. This meshed with Raffael’s own deep responses to, and regard for, the natural world.

After graduate school, Raffael joined the textile design studio of Jack Prince (which was also an important starting point for Carolyn Brady, Audrey Flack and other artists of that generation). Raffael recalls that in the Prince studio he learned the discipline of draftsmanship (providing the opportunity to exercise and strengthen his ability to draw), to work within the limits of a project, and to reproduce colors exactly. This experience, combined with a Fulbright to Italy, and the encounter with the 14th and 15th century Italian masters, began to shake loose the overarching appeal abstraction held for him. After some early experiments with figural subject matter, his mature pictorial vocabulary began to formulate.

For about a decade, he focused, among other things, on solitary images in monumental scale of heads of ancient statuary (Buddha), native American Indians, and animals, as a way of understanding the ancient view of the infinite and of the making of art as a product of a spiritual activity.

Trips to Asia, the challenging experiences of life threatening illnesses, death of close family members, the breakdown of a first marriage, the clatter of the commercial aspects of art all, ultimately, have driven him to the solace offered by the essence of Nature and to the paring down of his own psyche to its essential self.

And it is through his psyche that Joseph Raffael, the artist, moves from consciousness to a state of heightened subconscious awareness as he seeks to identify the essence of an object or of a state of being, and to make it tangible. He searches for imagery that will touch not only his but the viewers own subconscious as well, imagery that will stir the soul.

He seeks through his art to arouse recognition of the archetypal, of the divine, in the accidentals of the natural world.

His imagery, medium and technique work in concert and are tuned in this resolve - birds, flowers, landscape, color, light, and brushwork become the symbols of love, beauty, innocence, divine fragrance, peace, order, mystery, and the ephemeral.

Raffael has stated it most clearly. “Painting is the subject of my work, and nature the inspiration.” ("Interview with Joseph Raffael," Joseph Raffael: A Dream Remembered, Nancy Hoffman Gallery, catalogue for the exhibition, 1986, p. 6.)

Raffael’s imagery was more obviously stated in his early work, his symbolism more direct: for example, bird = spirit; a Japanese shrine in a winter landscape = serenity.

These more literal elements have given way in the later work to the physical dynamics of imaging (light, color, energy, quality of rendering), and to a new maturity of vision that underpins the image. In a number of earlier paintings, highly defined borders of abstract form and visionary color framed the central image (perhaps suggested, in part, by the work of his teacher Josef Albers), as if the picture were the meeting point of two different realities.

In such paintings as After the Rain, An Iris with Border (Seavest Collection), for example, these borders seem to have metamorphosed into the ephemeral backgrounds of his floral

and still life pictures, creating a more homogeneous tension between planes in and out of focus.

These backgrounds with a quality of light diffused as if through stained glass, identify a realm somewhere between the terrestrial and the celestial, between the tangible and the ideal. In these stunning images beauty and opulence unabashedly confront the viewer, and scale overwhelms. Composition, line, color, and brushwork have an emotional/spiritual pitch.

The image – whether of a flower resplendent in its full maturity, or of Lannis whose physicality is dissolved in the floral array of a favored dress,

or of koi stirring the surface of a pond (Before Solstice,Seavest Collection) - intoxicates.

Raffael’s work is not easily categorized, though associations with the Post Impressionists, Symbolists, Naturalists, Expressionists and even Photorealists have been offered.

To the point here, is the fact that Raffael does use photographs as an aid in the process of creating an image. But in distinction to other of his Realist colleagues who also employ photographs in their creative process, Raphael uses them as a vehicle of meditation, not so much as Photorealism than as a sort of Photo-transcendentalism.

In fact, for a very long time Raffael painted exclusively in the dark, with only a slide projected onto a small screen located next to the surface on which he was about to paint.

The solitary image lit brightly from behind has allowed him to extract the electric, prismatic effect of blues and reds, and to understand the advantage of enhanced luminosity.

It has contributed to the development of his special palette and versatile, expressive brushwork, which are ultimately in service to the description of the extraordinary colors, emanations and essence of Nature herself.

Raffael draws inspiration from another modern art form as well - cinema.

He is a great fan of the big screen, and seeks in the exploded, super scale and resonance of his own paintings to impart something of the impact and story line of movies in a single startling image.

As evidenced by the paintings by Raffael that illustrate this essay, the breakdown of the surfaces of objects seen at close range into a network of variously pitched and colored marks has the optical effect of scintillating energy.

This quality of imaging draws us from normal vision into our mind's eye, and seeks to convey non-verbal, mystical experiences with Nature.

Raffael works comfortably in acrylic, but tends to prefer watercolor.

Watercolor offers him a more direct echo of the unrepeatable and unpredictable events in nature, for example, the split second that light or rain momentarily transform a leaf or petal, or that just beneath the water’s surface koi,never touching, glide effortlessly past each other like molten gold.

While Raffael’s pictorial surface can at times be Impressionistic, at times Expressionistic, his artistic intent places him in the tradition - from antiquity to the Symbolists, to those similarly inspired 20th century masters - of artist as seer.

As such, his art might be viewed as transcending not only the material sphere but the temporal one as well,

offering a glimpse of the visionary in the often vacuous culture of the late 20th century

much as Blake, Redon or Kandinsky had sought to in their own troubled worlds.

©by Virginia Anne Bonito, "Get Real: Contemporary American Realism from the Seavest Collection" Raffael essay, DUMA, 1998, pp. 104 – 108; revised for the Seavest Collection Webpage and in-house Catalogue, May 2, 2000.

This essay is reprinted with permission of the author.